Audio / video: peertube.intrapology.com/w/t2NTBsU…

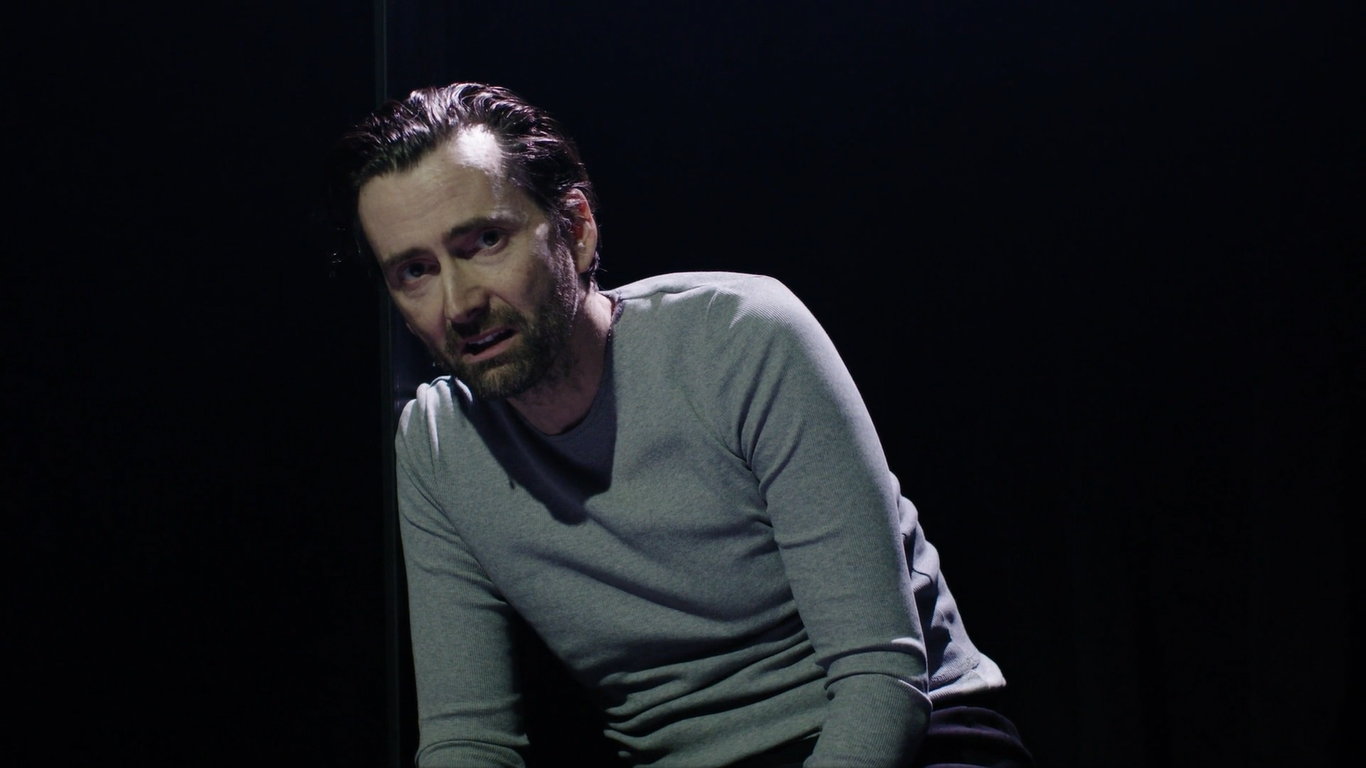

Last week, I saw a National Theatre Live cinema screening of Max Webster’s Macbeth starring David Tennant and Cush Jumbo, with a friend who was recently studying the play for his Access to Higher Education course. After a lifetime of health woes, caused in part by the cycle of burnout all too familiar to neurodivergent and disabled workers, he’s taking a personal risk by re-entering education, in the hope that it will give him the tools to build a working life that is more sustainable and fulfilling.

Returning to education has been a complicated experience for him. On the one hand, he has discovered a passion for Shakespeare that was out of reach when he was a teenager with unaccommodated disabilities. On the other hand, he has been persistently bullied by a teacher who openly supports the far right, and who from day one seems to have pegged him as one of her worldview’s recogniseable strangers, having immediately launched into a soliloquy about benefit claimants having it too easy. My friend knows so much more about the benefits system than this teacher could ever know even if she were inclined to learn, but he also knows a lot about managing people who have power over him, and wisely chose not to get in the way of a monologue by someone entering her villain era. One would hope that a Daily Mail reader’s prejudices would be sated by someone working hard to rise above his circumstances, but instead, she has chosen to embody The Circumstances.

The Circumstances can act through any of us.

Macbeth is about ambition, and the Donmar Warehouse staging had me contemplating where Macbeth’s ambition comes from. The almost entirely monochromatic costumes and stage establish a clear figure-ground relation early on, black and grey clad actors on a paper-white stage. This black/white arrangement brought to mind the dyadic themes of the play - light/dark, nature/culture, male/female, ambition/loyalty, destiny/agency. The Circumstances, and the individual who rises above them. With the witches portrayed as disembodied voices, the initial prediction of Macbeth’s rise seems to come from the earth itself, rather than from any individual.

Then we're introduced to Cush Jumbo's Lady Macbeth, the only character dressed all in white, a floor-length gown giving the impression that she has risen up from the ground itself, a force of nature. She embodies The Circumstances. When Macbeth decides that loyalty is more important than his own "black and deep desire", and Lady Macbeth persuades him to eschew "the milk of human kindness" in favour of something greater that awaits him, it feels like the same natural forces that first issued his call to action are reinforcing their message through her. By the end, when blood red has broken the monochromatic palette, he seems to have become merely a tool of someone or something outside of himself. In the end it means nothing. Did he ever really want power? What for? And how many people have to be hurt for him to protect this position?

The Donmar Warehouse Macbeth show, and its subsequent run at the Harold Pinter Theatre, were picketed by long COVID advocacy group Protect the Heart of the Arts, who chose the show as the focus of their campaign because of its historical circumstances, in connection to the Great Plague - when it was first performed in 1606, an outbreak forced theatres to close for eight months. It then repeatedly made the news due to its interruptions. On one occasion, the show had to stop partway through because a cast member suddenly lost her voice. On another, shows were cancelled for four days due to unspecified cast illness. A disorderly outburst from an audience member who was unable to return to their seat after needing to use the toilet may reflect a population-level neurological shift brought about by COVID, as many theatres are experiencing worsening audience behaviour in the 2020s.

(I must admit, I have some sympathy for the disruptive audience member’s complaint that they paid £250 for a ticket and then had to miss the performance because there was no intermission or toilet break - I missed “out out black spot” because I had to use the toilet. Thankfully, the cinema is a relatively accessible space that you can leave and re-enter as needed, and also the tickets only cost a tenth of what this guy paid.)

Whenever I think about people’s reluctance to adopt long-term infection control measures, I wonder if it’s because of a collective violence that we’ve normalised on a deep level. Is the issue really that people simply don’t know that COVID does cumulative, long-term damage to the body? Or is it an ingrained ableist attitude that attributes inherent value to a person’s ability to endure the long-term strain of a creative career? The figure-ground relation shapes the stories we tell to justify this ableism.

On one hand, attributing a phenomenon to the natural world can allow us to wash our hands of responsibility. Long COVID in the creative sector may be a similar social phenomenon to burnout. We all collectively contribute to the conditions that cause it, but rather than seeing this as a collective harm that is being done to the bodies of our peers, we treat it as though it were a natural process of filtering out those who inherently lack staying power. It’s difficult to get data on how many people in the performing arts have been impacted by long COVID, just as it’s difficult to estimate how many people could have made beautiful contributions to our culture if they hadn’t been driven past the point of exhaustion by a working culture that demands everything you have and rarely gives you a living wage in return. Are The Circumstances natural phenomena, or are they the results of man-made systems that prize ambition over solidarity?

On the other hand, viewing ourselves as heroic individuals can allow us to ignore the forces beyond our control. In the face of uncertainty and alienation, when you know that talent is almost meaningless, your personal endurance can seem like the only thing left to rely upon. And yet, endurance isn’t really a matter of personal agency, because the individual is a cultural construct. Like the black costumes against a white stage, we use a number of everyday narrative techniques to reinforce the myth of the individual. COVID and its attendant Circumstances show us that our own agency is only a small part of the picture. Unseen non-human actants can elevate us or bring us down, while appearing to take the form of individual free will. The greatest influence we have on them requires collective action in solidarity with one another.

Protect the Heart of the Arts are arguing for greater COVID mitigation measures to be taken by theatres, including requiring masks at a select number of performances, providing in-house PCR testing for the cast and crew, and improving ventilation. These are very reasonable measures. Masked performances would at least allow more chronically ill and disabled people to attend, an infection-control corollary to relaxed performances that incorporate accommodation measures for sensory needs. On-site PCR testing machines such as the PlusLife are expensive for individual households, but reasonably priced for large organisations. Similarly, improving ventilation is an expensive task, but with proper support from public funds or private philanthropy, would significantly improve safety for audiences and crew.

So much of how we talk about mitigation measures rests on the figure of the vulnerable person, who is more likely to be harmed by a COVID infection. I use this narrative device myself often, because I am considered vulnerable due to my MS disease modifying drug, which works by killing all mature B-cells from my immune system. It’s easier to make the case for mitigation measures when I say that I’m just advocating for my own needs. But in reality, this isn’t about individuals. The number of people living with post-viral energy-limiting conditions has skyrocketed in the 2020s. Anyone can develop Long COVID.

The Circumstances can act through any one of us. We are part of the world, the world acts through us, and we are collectively building a mass-disabling world. Is it all worth it, for the ambitions of a few winners?